Illumination of the Flesh

In the early eighth century, an Anglo-Saxon abbot named Ceolfrith died en route to Rome while accompanying a manuscript produced as a gift for Pope Gregory II.

His monastery of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow had been the center of the period’s monastic movement in northern England, one that began a history of fluctuating fortunes for medieval learning in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The manuscript in question was one of three Vulgate Bibles the monastery produced, for which 2,000 heads of cattle had been raised in a massive undertaking led by Ceolfrith. The Bible’s size, at nearly 50 cm high, 34 cm wide and 18 cm thick, weighed nearly 75 pounds, made it one of the largest such documents that still survives today. A self-evidently ambitious project, it was Ceolfrith’s misfortune to pass from this world just ahead of receiving his due glory.

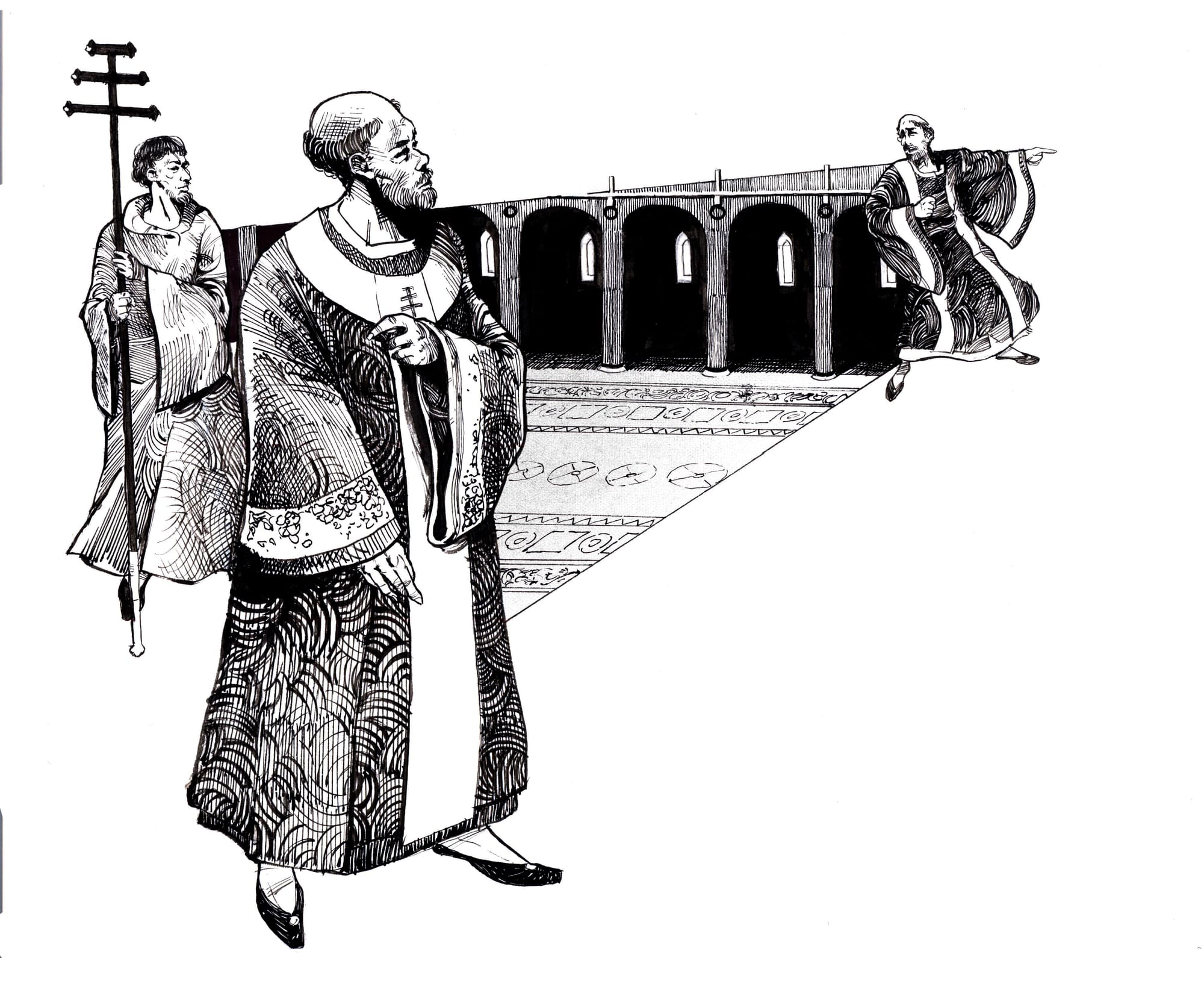

Aeswith, the ill-fated monk of Illumination of the Flesh, would have produced his work around the same period and in the same location. However, I was unfamiliar with Ceolfrith’s tale when writing my own, my inspiration having come from the story of the Lindisfarne Gospel, a similarly celebrated and extant manuscript. At around the same time Ceolfrith’s bibles were in production, the bishop of Lindisfarne monastery, Eadfrith, laboured away on his own collection of the four gospels. It’s a beautiful work, combining Latin, Anglo-Saxon and Celtic elements into meticulously crafted illuminations that is today considered a masterpiece. Perhaps most notably, Eadfrith was the sole scribe and artist, and had been at work on the manuscript for ten years when he passed away before its completion.

The richness of monastic learning and production in northern England at this time led to the emergence of works of comparable craft and beauty. Gifts of manuscripts to Rome were also common enough, as the Western Church’s capital exercised ecclesiastical authority over the Anglo-Saxon churches. Over a century earlier, Latin missionaries had begun arriving in increasing numbers to Britain, establishing churches and converting the pagan locals. By the 8th century, Christianity was the dominant religion in most of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Christianity, of course, had first arrived in Britain via the Romans at least 600 years earlier, and in that time a mosaic of local variations in Christian practice and doctrine had developed. Pockets of paganism also survived. English monasticism’s scholarly and artistic successes in the 7th and 8th centuries owe much to the intermingling of these influences.

It’s in this context that the physically and spiritually tormented Aeswith produced his manuscript. The supernatural impetus for its production was my invention, so I’ll briefly outline what would have driven the poor monk to such extremes by exploring the superstitious and material realities of his world.

Life in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms was challenging, to put it mildly. The archaeological evidence from gravesites indicate just how commonplace malnourishment and disease were. Amidst oppressively high rates of infant mortality, those fortunate enough to survive into childhood and beyond entered into a life of rigid hierarchy further constrained by tenuous health and political circumstances. Near-constant conflict between kings and petty lords encouraged a martial culture. It was rare that any but the largest kingdoms could maintain a standing army, thus it was the duty of all able-bodied males to fight for their lord. Boys as young as twelve were drafted into local militias called fyrds. The early eighth century laws of King Ine of Wessex specified that boys should begin their military training at seven years of age, to last until the age of 15.

It’s not difficult to imagine the suffering such a policy invited for young boys, but then the demands on a young person were vastly different in this era. Nevertheless, for a soul like Aeswith, drawn as he was to a life of quiet prayer, the guilt over having committed what he regarded as outright murder was powerful enough to mark him to the end of his life, which he gave in its entirety to the expiation of his crime’s stain. Aeswith wasn’t alone in recognising the injustice of these circumstances. In the mid-6th century, Romano-British monk Gildas wrote,

“Britain has kings, but they are tyrants; she has judges, but unrighteous ones; generally engaged in plunder and rapine, but always preying on the innocent; whenever they exert themselves to avenge or protect, it is sure to be in favour of robbers and criminals…”

Unjust though these circumstances were, monasticism didn’t seek to revolutionise the world. Rather, it sought to retire from it. For the world, it was believed, had been made by God as a prelude to a more perfect hereafter. If there was suffering in it, this was God’s intent as a means to share in the experience of Christ. Whether the Latin church believed God capable of cursing someone (as Aeswith believed) is doubtful, opposed as it was to the magic and superstitions of Britain’s Celts and pagans. But the creative richness from which the manuscripts of this period arose was precisely the result of these traditions’ intermingling.

Though Christianization had firmly taken hold in England in the 8th century, superstition lingered in the countryside and among common folk. Fairies and other mythical creatures, magic talismans, sacred wells and springs, even curses, though fading in importance, remained widespread enough to flavour Christian practice.

It’s in this nebulous space between cultures as they influenced the minds and imaginations of common people over many centuries that Aeswith’s own curse maintains some plausibility. He is a man in conflict with himself, his world and the period in which he finds himself.